Sustainababble

Hunting for a cheap to heat house?

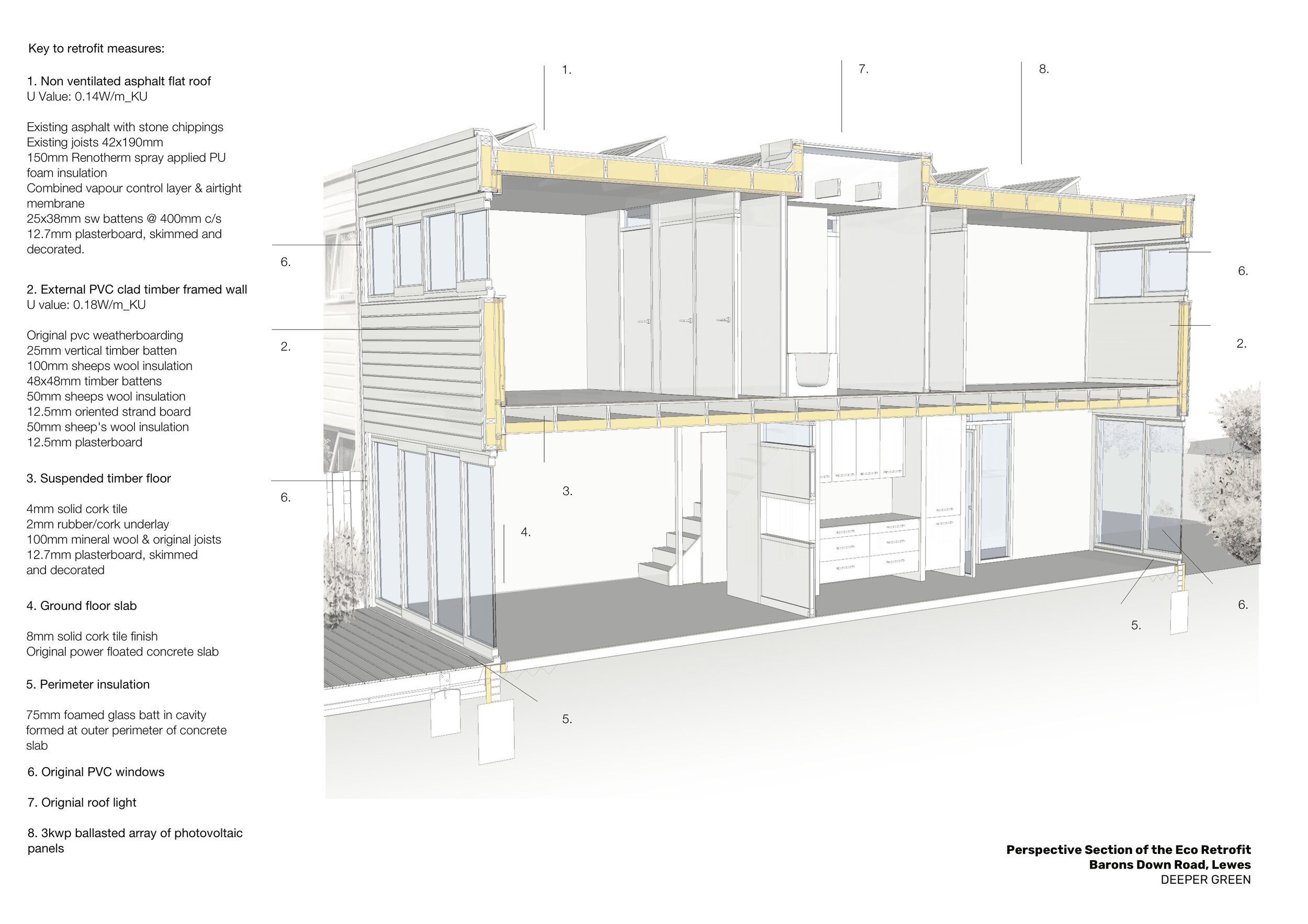

Above: The award winning eco-retrofit of a 1960’s built timber frame house in Lewes, East Sussex as shown in a sectional perspective. For a budget of less than £70K including solar panels and VAT, the house was made virtually carbon neutral and almost energy cost neutral. As a mid-terrace flat roofed timber framed house, it was an ideal candidate for cost effect eco-refurbishment.

With the advent of the new PAS2035 – Specification for the Energy Retrofit of Domestic Buildings, the UK is having another go at mass eco-retrofit. Here are some top tips towards a successful eco-retrofit starting with what kind of property you should try and find if you fancy having a go.

Don’t stretch your budget too thinly

It is fair to say that the most common enquiry an architect will receive in the private residential sector is a couple who have bought a house and they want to add an extension and they want to make the rest of the house more energy efficient. Nine times out of ten, their budget will be insufficient to do both elements well and normally they end up just making the extension and the house remains expensive to heat. Everyone wants more space of course and whilst people can afford their energy bills, they will likely go for the extension over the eco-retrofit when push comes to a budgetary shove. Perhaps in the energy starved future ‘adding value’ to a house in real estate terms will not just be about how many additional rooms you may have added but to demonstrably show how energy efficient and cost effective the building is to live in.

The less surface area the better

A terrace house is one of the most cost effective typologies you can get as you only really need to treat the external facing elements of the ‘thermal envelope’. It is even better if it has a well orientated (within 30º of due south) pitched roof facing south either on the front or garden elevations.

The humble mid-terraced property is your best bet because you simply have less external wall to insulate. However, be careful of terraced housing with large rear extensions (also known as ‘outriggers) – with their shallow but long floor plans and lots of external walls they are particularly parky in winter. If you have a detached, semi-detached or end of terraced property, you will have more external surface area to treat.

Steer clear of charming but fussy architectural detailing

Sadly, if the property has lots of charming but fussy architectural articulation, this will likely be expensive to deal with when it comes to insulating the walls. If it is on the outside you may also find the local authority are not too keen on you changing it or covering it over. If you are insulating on the inside, you may override the charm of the period features or need to have them reinstated with a small loss of floor area.

Eke out a timber frame

Importantly for a refurbishment, it is usually easier to carry out an energy efficient refurbishment on a timber frame building than on a masonry one and the key to that is ensuring you keep the constructions BREATHABLE. However, in the UK there has been a lot of predominantly unwarranted resistance to timber frame construction. It is true a lightweight timber frame building can be prone to overheating if the glazing is poorly protected against too much unwanted solar gain and/or the structure is under insulated. That said it is quick and easy to heat up.

There are a lot of people who espouse the benefit of heavy thermal mass when it comes to energy efficiency – solid brick, stone, blockwork or concrete will give you that. The idea being is that once you’ve loaded up the internal fabric with the heat energy or ‘coolth’ to provide thermal comfort, the building will not be too much affected by big fluctuations in outside air temperature between day and night. Of course, this also means you have to insulate to the outside of the mass really well, so your building does not hemorrhage the energy. This has to be taken with moderation. Too much thermal mass will give you internal condensation issues, particularly in the warm season – counterintuitive though it may seem. It will be interesting to see what the insurance industry makes of poorly conceived eco-retrofits of traditional brick buildings relative to well-designed timber framed houses in the years to come.

Try to avoid buildings where internal insulation is the only allowable solution

In many instance, insulating an existing external wall is only practicable from the inside. In this case it is solid brick.

When it comes to insulating external walls, it is always more efficient and technically safer to insulate on the outside of a property than on the inside faces. If you insulate the inside faces you will have the risk of creating stale moisture behind the cladding and this may lead to mould growth and possibly fungal attack of the building fabric. Conservationists should take note that if you insist on a brick or stone building being insulated internally, that stone or brick will stay colder and wetter for longer with an increased risk of frost damage. If you have timber joists socketed into the brick, these should be cut back and the load transferred to the sidewalls and that is expensive to execute. The best type of internal insulation is a breathable one. If you can get the moisture in the wall to transpire to the inside as well as the outside, it should be safer. The only other watch point is not to insulate internally too much. Super insulating on the inside of a masonry building will increase the risk of defects arising. The aim should be to just to take the edge off those ‘stone cold’ surface finishes. Calcium silicate boards, timber fibre insulation with lime plaster and cork linings or cork plaster can achieve just that.

Hunt for a property with plenty of access to the sun

Roof typologies which are well suited to collecting free solar energy.

If you want to take advantage of free energy from the sun, look for a property with plenty of sun. A south-facing slope with little overshadowing buildings or trees is ideal. Also check how the building is orientated with the sun. If you have large amounts of glazing facing south, then you can look forward to plenty of free passive solar heating in the colder months. South facing glazing is also easier to protect against too much solar gain in the warmer months with external blinds, shutters or even foliage. East and west are tricky as the sun is lower in the sky when it enters the glazing and easy horizontal solar shading solutions above the glass do not tend to work. Large amounts of west facing glazing are perhaps to be avoided or changed. Check out the roof and make sure it can accept plenty of solar panels with minimal overshadowing and predominantly facing south. Hips, dormers and chimneys are not great when it comes to an efficient array of solar panels.

Awkward roof forms will also tend to limit the amount and the efficiency of a solar panel installation.

Glazing

If heritage styling is important, remember that it can negatively effect the outcome of a property’s potential to exploit natural daylight and beneficial solar gains.

For years, double glazing was always seen as one of the biggest energy-saving features you could install on a property. Nowadays, almost all dwellings in the UK have double if not triple glazing so it is a case of diminishing returns if you replace knackered units. One good rule of thumb with glazing is to maximise glazing on the south side (as mentioned above) and have smaller penetrations on the east, west and north elevations. Some energy consultants also promote running with double glazing on the south side and having triple glazing on the other elevations. If the passive solar gain on the south side works well through the year then this makes a lot of sense as triple glazing will actually reduce the solar gain coming through. Triple glazing is more expensive than double glazing, but it may surprise many at how little extra it is.

Heating and power

In 2020 the electricity grid is only partially decarbonized. Until it is more fully carbon neutral, if your property has mains gas, you might be best off sticking with a high efficiency gas condensing boiler for a little longer. Heat pumps work off electricity and crudely they work a little like a refrigerator in transferring heat away from either outside air, the ground or a body of water and, with a bit thermo-dynamic magic, dump that heat into your space heating and domestic hot water tank. The technology is still very expensive to purchase compared with a gas boiler and, until the grid is more fully decarbonized, it is perhaps more carbon beneficial to stick with a gas boiler, although that argument will not be valid for much longer.

Solar thermal panels are good value. If you have room to mount a couple of panels on the roof and have a hot water cylinder in the house, you can get about 50% to 60% of your dwelling’s domestic hot water needs through a solar thermal installation.

Solar photovoltaic panels are the type that make electricity. That said, you need about 8 to 12 panels to have a worthwhile amount of power generated for a house. You also need what is called an inverter internally. This takes the DC power from the panels and converts it to AC power so it can go into the mains power supply and also be fed back into the grid. You can fit electric storage batteries or dump excess electricity into your hot water cylinder, though arguably that is a very poor conversion of energy.

In traditional central heated house, we have relied on a boiler using bio-mass or fossil fuel to provide the heat energy input to provide thermal comfort when the rate of heat loss through the building’s fabric in cold weather starts to accelerate.

In a super-insulated house the rate of heat loss is slowed down to such a point that in some instances it is possible to heat the building with body warmth, cooking and the odd electric heater. This is the principle behind the Passivhaus standard. To do this with a retrofit project is a big and possibly very expensive undertaking.

It is always worth remembering when thinking about heating and power, the so-called, ‘fabric first’ principle. That is to say, try and get the heating and power load of the building as low as practicable before you look at other technology.

Ventilation

It is important to ventilate your habitable spaces. Stale air can be unhealthy for the occupants. In winter, even if you have a well-insulated house, you still have to bring in cold fresh air. For this reason, you might want to consider mechanical ventilation. If you do a really good low carbon refurbishment, you should also try and eradicate unwanted air leaks through the fabric of the building – areas between external windows, doors and walls or service penetrations. If you can get the air leakage rate down to under one air change per hour (difficult to do) then you might want to consider mechanical ventilation with heat recovery. This expensive and very invasive technology may not be all that practicable to install in an existing building as you have to run air ducts to the habitable rooms, bathrooms and kitchen. It is however considered more energy efficient than passive ventilation. If your budget or the constraints of the project do not allow for this, ensure the glazing installed has trickle vents.

Low energy lighting

The advent of LED lighting technology has revolutionized how we light buildings in recent years. Even in the early 2000’s LED lighting was not really capable of being the main lighting source for a room. They just were not bright enough. All that has changed. They provide superb quality and quantity of light without flicker and incredibly long service life – no more changing bulbs. Best of all though is how much more energy efficient they are than the old tungsten filament lamps. You can light a three-bedroom house for under 200 Watts!

Climate change adaptation

The experts say our weather patterns will change quite significantly over time. There will be longer and more intense periods of sun and rain that in turn will stress a building’s fabric yet further. Rainwater goods may need to be replaced with larger profiles to handle more intense rain events. Increased ultraviolet intensity will accelerate the degradation of some external materials. Older buildings may yet perform better than some of our more recent commercial offerings particularly in protecting the occupants against unbearable overheating. If many of our houses then require energy for comfort cooling in the summer as well as for heating in the winter, our efforts towards creating cheap to heat buildings will be environmentally meaningless.