Retrospective Futures; Futurehouse

The double height glazed space of Futurehouse still provides passive solar heat for the house.

Introduction

It is the 28th September 2022 and I am on a train heading home after seeing my first built project after what must be 28 years. They say you should never go back to your old school and I’m sure the same is true for an architect visiting an old project. I think this must be especially true if it is a house. Afterall, it could well have been in the hands of many different owners since, all of whom wanting to make their mark. Still the significance of this visit was not to be missed. The building in question was Futurehouse and it was a competition winning project that launched the careers of myself and my old friend and collaborator, Duncan Baker-Brown. It was to become a show home at a housing expo in Milton Keynes and the last of which organised by the Commission for New Towns. Moreover, I was to meet the current occupier and engage in a filmed discussion for a ‘living archive’ being compiled for the city council. I suppose what was most interesting for me was to revisit a project which was all about envisioning the future. Now that we are in that future, I was nervously excited to find out just how well Futurehouse anticipated and provided for the lifestyles of our times.

Remarkably intact after 28 years and at least four different owners, the stairwell space at Futurehouse.

How did Futurehouse come about?

For years, Duncan and I would include Futurehouse in various talks that we gave, mentioning its design features and how it anticipated the energy and resource threatened future. Over time my own memories of how the project came about, particularly how it got financed and built became dormant. With the prospect of the living archive’s collation of material and the interview with the current owner, I felt the need to rummage through old archive material, brochures and press cuttings from 1993 and 1994 and refresh those recollections. As I reviewed these old documents I realised that there were important historical stories to tell; poignant socio-economic observations to make, particularly as regards how society viewed ‘green’ issues and how industry was responding and positioning itself to the growing awareness of our existential predicament.

Sketch impression of the competition entry.

How the story begins was remembered well enough. There was a RIBA competition announcement in Building Design magazine sometime in the first half of 1993 for a ‘house of the future’ with the intention to build the winning design for a Milton Keynes housing expo. I rang my co-student. Duncan Baker-Brown and asked if he wanted to enter it with me. At the time, which happened to be a very bad recession for the construction sector, we were part of only a small handful of students working in architectural practice, having just finished our diploma course in Architecture at Brighton Polytechnic. We were officially still ‘Part III students’ and not yet fully qualified architects. We entered the competition and, much to our genuine incredulity, we won.

From a social history point of view, the next part of the story is interesting and it is also the bit I had started to forget about. The backer of the housing expo was an East Sussex-based gentleman called, Richard Cunningham. Duncan and I went to meet him a short time after the announcement of the competition win at his home near Etchingham – a fine old stone-built manorial home. He wanted to meet these two ‘students’ who the RIBA judges had selected as the winners of the competition which he had commissioned the RIBA to facilitate. He was very genial and courteous but Duncan and I could tell he was not 100% sure about how the next bit was going to play out. Indeed, Cunningham’s biggest headache was not so much a question of whether or not these two students could now go onto prepare the construction information for their design (after all, Duncan already had years of experience in architectural practice, having started in his Uncle’s office at the age of 17), it was how to fund the build. I don’t think Duncan and I quite understood the full implications of what Cunningham must have said to us that day but in effect it was paving the way for the Federation of Petroleum Suppliers (FPS) to plug the finance gap such that the project could proceed to the build.

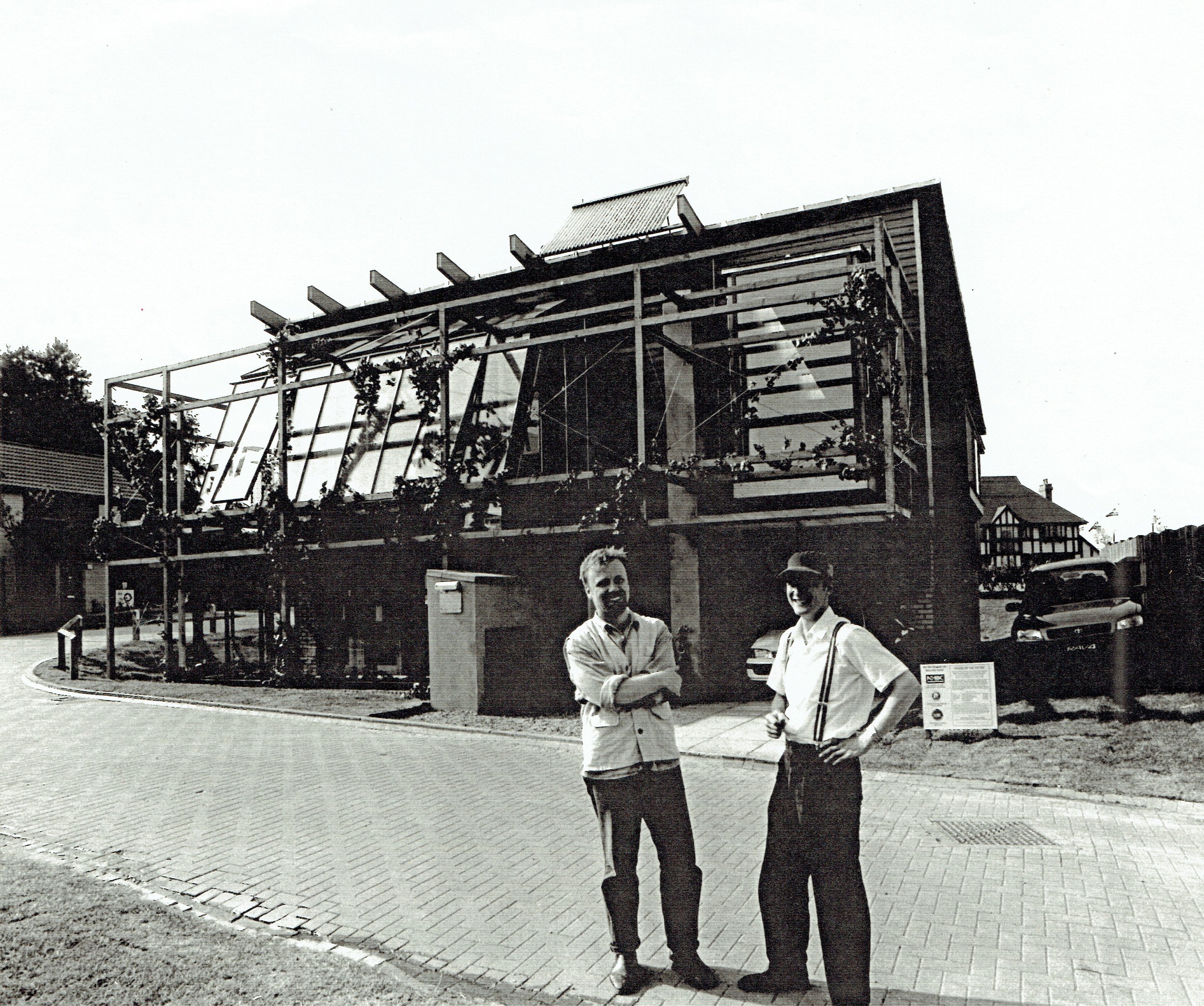

Duncan Baker-Brown and Ian McKay (right) outside Futurehouse during FutureWorld Housing Expo in late May 2004. The house was unfinished for sometime after the exhibtion despite some dubiously sourced sponsorship deals by the organisers.

It turns out that ‘big oil’ was very interested in being aligned with the ‘house of the future’ and they would go on to gear-up their marketing team to make it sound like the young eco-minded designers had chosen oil-fired heating for their vision. By the time it came to the housing expo’s opening, there was FPS literature all over the house and little framed posters standing on sills and worktops publicising oil as the fuel source of choice. Duncan and I would go up on the weekends to show visitors around with the bizarre bi-polar presentations of Baker-Brown McKay (BBM) giving one version of the overview and reps from FPS somewhere else in the building giving an entirely different take. As a form of cheeky environmental protest, we even turned the little free-standing posters face down as we went around.

A model-making student created a stunning cutaway 1:50 scale model of the house and its garden. It showed some of the key constructions and building services technologies employed.

So what future features did Futurehouse have?

The big win for BBM was that, apart from the oil-fired boiler and storage tank and that the purpose-designed landscape work which was never built, the rest of the house was pretty much spot-on in terms of what we originally set out to achieve. The building was thermally efficient, it had innovative passive solar heating and ventilation strategies, it was made from materials of low environmental impact and it had a solar thermal panel. Our big idea for a home working space was built. Blending ancient technologies with new, we even had an ambiently cooled pantry for the kitchen.

Thermal mass was a key consideration of the design with beam and block floors and an inner skin of concrete blocks and wrapped in a thick layer of insulation below a timber clad upper storey and brick skin ground storey.

We settled very quickly on the idea of a timber box sitting on a brick and block base. A timber frame on the upper floor and roof gave us opportunities to radically increase conventional insulation thicknesses of the day. The u-values still look impressive. We specified lime mortar as we wanted the bricks to be salvageable at some point in the future. We went with beam and block floors as the additional thermal mass we felt would be useful. In fact, even on the upper storey the 150mm deep timber frame merely forms an insulation cassette to the outside of a concrete block and plastered wall.

Internally, we chose as many natural materials as we could with timber and stone clad floors, hessian/wool carpets, paints with plant-based pigments and oils and Warmcell insulation which was recycled newsprint impregnated with gypsum and blown into the joist and stud zones.

Fulcrum engineering ran with the competition design for a double height glazed buffer zone and suggested it work in conjunction with an ambient conditioned plenum under the beam and block floor and augmented by a single fan blowing the conditioned air into the stairwell, through undercut doors to the outer rooms. Image source: CIBSE Journal.

Our initial competition-winning ideas for how the double-height conservatory would work in terms of pre-heating air for the house in the heating season were refined and added to by Fulcrum Engineering. They brought new ideas about how a double height glass space could be used to generate enough stack-effect to pull air through a plenum under the beam and block floor. This pre-cooled the air for summer and pre-warmed it for winter. A fan at the top of the central stairwell was introduced to push this tempered air into the house whereby it would slowly migrate to the outer rooms via under-cut doors. Placating our concerns about the oil-fired boiler, Fulcrum’s Andy Ford made a useful observation that for many households who do not have access to mains gas, this heating format was a helpful insight into what could be done with oil heating as a back-up to the passive measures. Nowadays of course, it would be all about electric heat pumps.

The original home work space anticipated the need for home-working in an age when information technology would replace energy and time hungry commuting.

A previous owner had converted the WC and tea station into a shower room such that the space was now being used as a master suite.

It was the home working space though that we felt was potentially the biggest energy-saving device in the scheme. Why commute everyday if you could telework instead? Just think of the energy savings and extra time you could have around home and with your family.

How was it received at the time

The exhibition coincided with something of a heatwave in the early summer of 1994. My overarching memory was of people entering Futurehouse and noticeably sighing in relief as they were greeted by the very evident ‘coolth’ afforded by the house. The attention to thermal mass and the ventilating effects of the double height conservatory, drawing cool air into the house from the underfloor plenum, it all worked a treat. On the last weekend visit we made, Duncan and myself toured some of the other houses on the expo site and verified personally what we had heard from visitors that a few of the other houses were not just over-heating but in one particular case the interiors were full of noxious off-gasing from its palette of overly processed petrochemical based materials.

The stairwell space in 1994.

The stairwell space in 2022, remarkably unchanged.

The extraordinary thing about our chats with visitors to the Futurehouse was the varying views about the prospect of working from home. It was a continuation of an idea I had as a degree student where my final project, a headquarters building for information technologists, did away with most of the brief’s office accommodation by arguing that in 21st Century with the need to reduce our energy use (and carbon -emissions) why have people commuting into work every day when they can use information technology to telework? Interestingly, again from a social history point of view, journalists completely got the point of home working as most of them were already doing it, but most members of the public could not see the point of it but they all concurred that it would make a fab ‘granny annexe’.

Wherever possible Futurehouse used bio-based or minimally processed materials in its construction palette.

Duncan had been particularly concerned about stories in the early nineties about sick building syndrome whereby the internal environments of modern buildings, with their petrochemical materials and poor ventilation systems, were giving rise to people having headaches and even inducing longer term ailments. With this in mind, we wanted to ensure that the building’s specification was made as much as possible out of natural materials wherever possible. Sadly, many of the more benign products and materials were only manufactured on the continent. In Germany bau-biology or building biology took off in the 70’s and 80’s with manufacturers responding to demand. The UK it seems just were not interested enough for it to become a mainstream construction sector. We would explain to visitors that using these materials was a good way to demonstrate their value and that in time a home-grown bio-based materials revolution would lift-off.

Futurehouse as photographed during FutureWorld in the summer of 1994.

What did we discuss at the interview

I was very excited to meet the current owner, David. Perhaps due to the anticipation that we both had about taking part in a filmed discussion, we were probably both a little nervous. We had no idea how that chat was going to unfold. He explained why he and his wife bought the house, the features they liked etc. He asked what I felt about all the changes that I had just seen in my walk-through. “I had mentally prepared for just about anything”, I said. Curiously, some aspects of the house, particularly around the stairwell were remarkably unchanged.

We tried between us to work out how many owners the house had acquired. I knew that the first owner of the house was an engineer and he was specifically interested in the house as he wanted to use the home working facility for his office. Together we reckoned that he and his wife were the fourth owners of the house.

Ian McKay (right) with Futurehouse’s current owner David Richardson looking at an original dye-line drawing from the construction information.

One of the highlights for me was when I discovered he worked from home. Although a previous owner had converted the home working space to a master suite, David said he worked from home pretty much all the time now and from one of the smaller bedrooms. I asked if he started to work from home after the lockdowns and he confirmed that was indeed the case. “It is so amazing that nearly the whole country pretty much overnight started to work from home”. I went onto explain that after Futurehouse, BBM launched a hypothetical urban design project called Cityvision whereby we proposed that in 30 years time, 30% of the working population would work from home 30% of the time and then charged ourselves with looking at the built environment impacts necessary to support that change. Here we are nearly 30 years later and I suspect we have more than 30% working from home and more than 30% of the time.

The back garden was never realised but it formed an integral part of the overall concept design with the house appearing as a timber box perched atop a garden brick walls. The water cycle was symbolically replicated with roof rainwater catchment leading to gutters and rils before dropping into an upper and lower pond. The view from the home working space was heavily bracketed by the pergola to give the impression you were away from the domestic realm.

…and the lessons learned

I must have done a good job bracing myself for what I might have encountered at a house project I was an author of from so long ago. I was not eternally scarred by what I found. There were somethings which were a little disappointing but, overall, it was incredibly interesting to see how four different homeowners had left their mark on it and how somethings still worked while other aspects were sorely in need of replacement or TLC.

David asked at the end of the chat, “what would you have done differently?” Great question, I thought. I said, “I wished that we had designed a simpler and cheaper to create garden.” I also mentioned that if doing it in this era, we would have almost certainly have given the house an MVHR ventilation system and an ground or air source heat pump for the primary heating source.

One negative point of reflection I thought of is that it is such a shame that nearly three decades on and we are still having to make excuses for specifying environment-conscious products which are still only available from the continent. The home-grown supply chain is nearly 100% hooked on petroleum-based material content. We had to then and still have to post-rationalise by arguing that one day such materials will be manufactured on these islands and for now we just have to spread the word.

In retrospect it was more important to get the house built than not. OK, there was oil money involved and ‘petroleum’ and ‘sustainability’ were being talked about in the publicity but overall, the other stories we were able to tell outweighed that somewhat embarrassing episode. It was a lesson in compromise and best of all, the oil-fired boiler and its enormous storage tank had long gone. We were after all transitioning out of the age of fossil fuels.

Early concept sketch for Futurehouse showing the idea for the low pitch roof letting sun into a ramped garden with solar panels held out on the south side of the house forming part of a double height glazed buffer zone. In retrospect, a less heavily engineered garden would have had a better chance of making into reality.

Futureworld ‘archive-opia’ filmed interview with Ian McKay and current owner. Film by Roger Kitchen and Alison Davies.